Happy path programming (Part 1)

What can we learn from notebook programming?

Like many engineers, I've spent time working with the programming language Python and with interactive Jupyter Notebooks. Together, these two tools are the industry-standard toolkit for Data Science and Machine Learning. I really enjoy the interactive nature of notebook coding; but one of the reasons I've focused my career towards software engineering - rather than other specialties - is because I've observed that many organisations have their biggest problem with the quality of their engineering, rather than the ingenuity of their analyses.

In the back of my mind though, this always leaves a big unanswered question:

How do we close the gap between code experiments, and robust software?

In this part of the post, I'd like to start by summarising the problem.

Notebook programming - it's about the process

Firstly, what does notebook programming look like in the abstract? I'd characterise it as having a few properties:

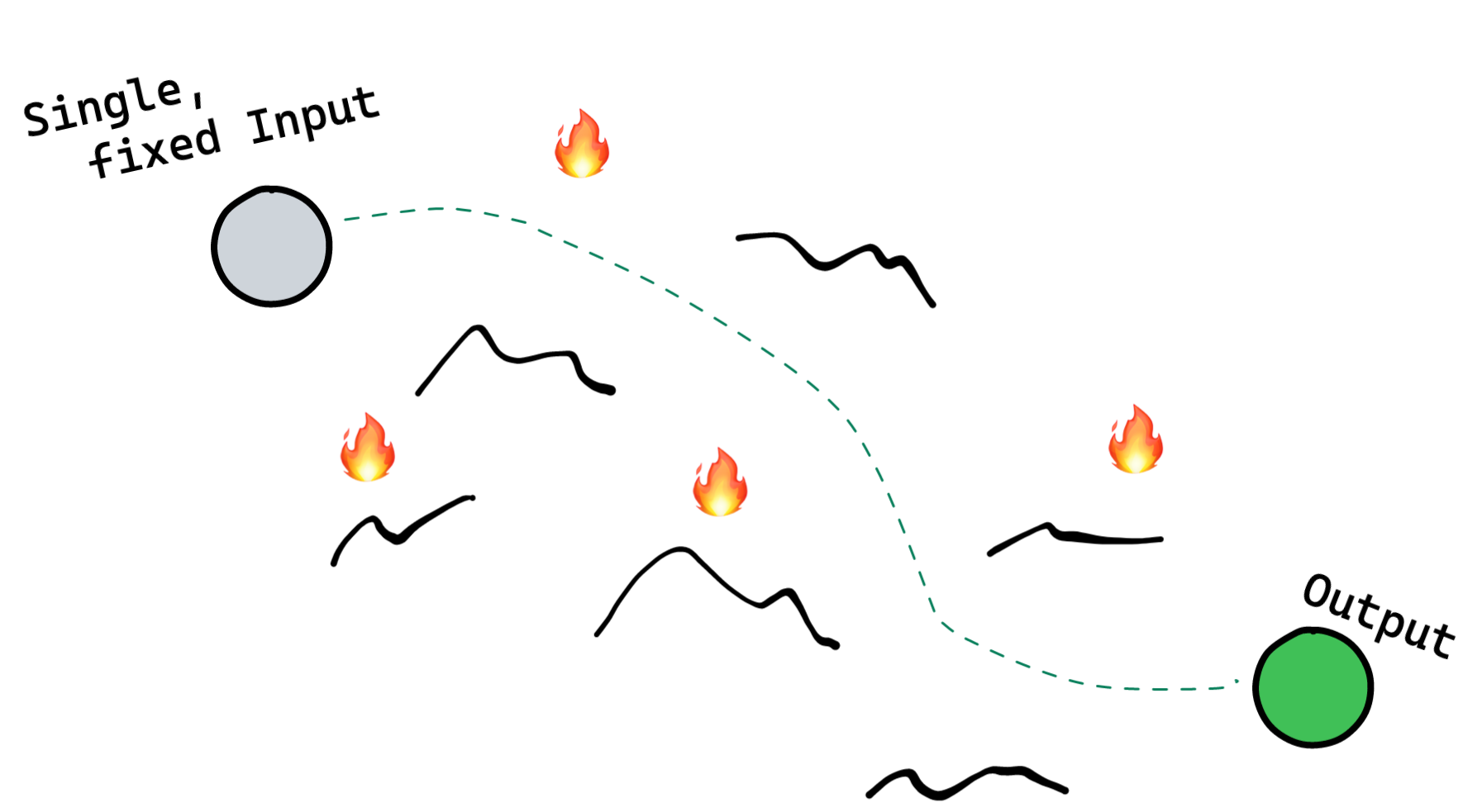

- Startpoint - Typically a 'single' known input, such as a CSV or dataset

- Endpoint - Some desired output, such as a chart or trained model

- Process - An iterative process of finding a path between the two

That intentionally oversimplifies a lot! Amongst other things:

- There are often many hidden inputs, like REST APIs or other enrichment dependencies. Those dependencies are alive and working at the point the notebook is created, and so they are broadly treated as additional 'known' inputs

- The 'desired output' may also not be clearly defined at the start, since the work is often investigative. We might only know the 'endpoint' when we reach it.

Broadly, once the notebook process has been completed, we have our happy path, but we probably shouldn't stray from it:

Software programming - it's about the destination

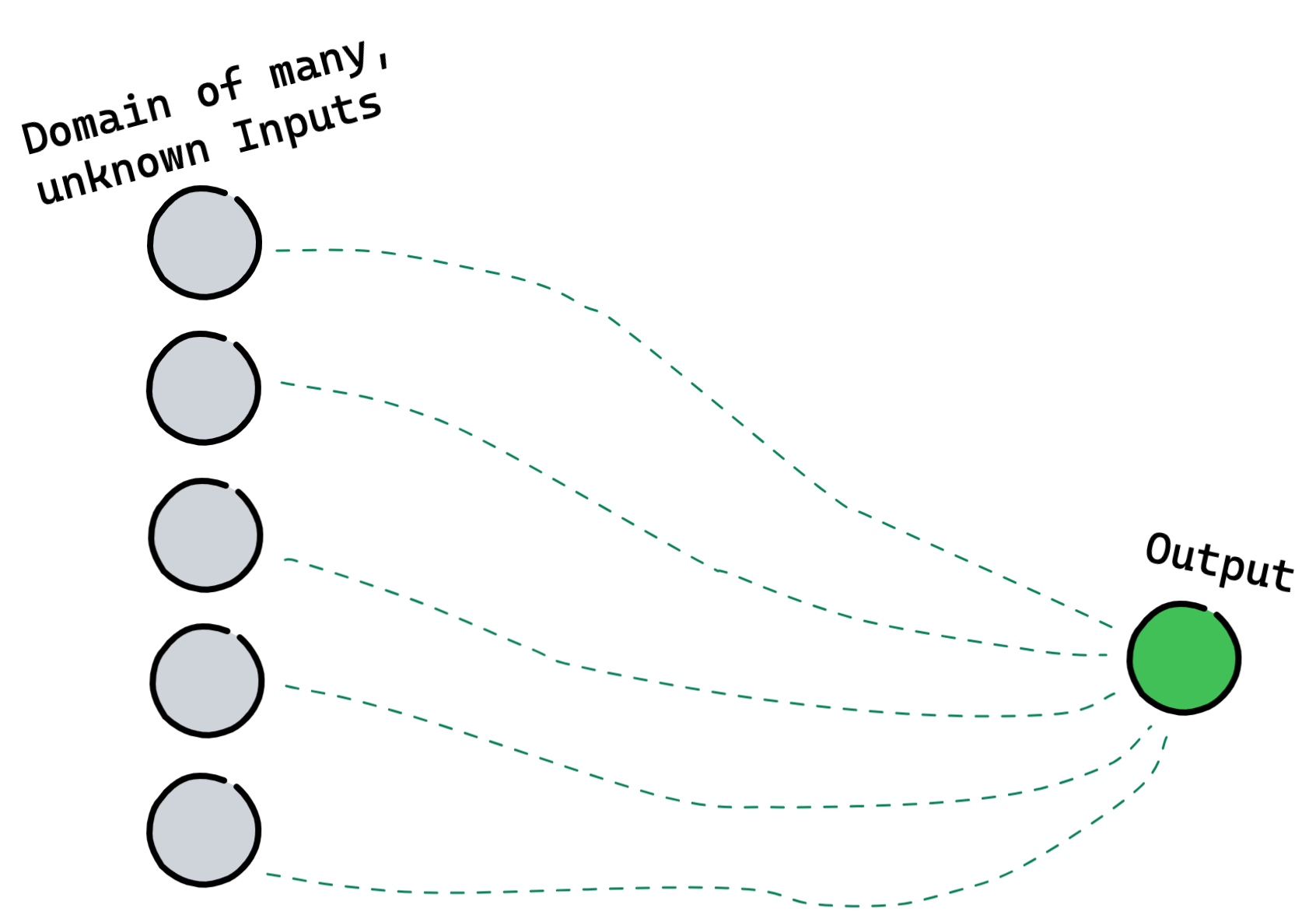

The goal production-ready software is to widen the set of happy paths available. To be more resilient to unexpected inputs, and to produce some desired output a greater percentage of the time:

We want to be able to get to a rational output even when one of our inputs or dependencies isn't working in the way we'd expect. This 'rational output' may simply be an error message, but generating it correctly matters.

From this perspective, we can state the problem as: how can we interactively pursue our happy path, while at the same time ensuring we eventually deliver a wide set of well-handled code paths?

⏳ Next time

In Part 2 of this post, I'll lay out a few of my own disparate ideas about how we could think about bridging the gap between these two software development styles.